[ad_1]

Let’s face it, we’ve all admitted that a certain movie, or a song, or even a certain food is our “guilty pleasure.” But what exactly does it mean? When we refer to a guilty pleasure, we could be talking about something that is strange or lowbrow, or that others might disagree with; something we love secretly, that others either dislike or couldn’t believe we would like, something that we are way too embarrassed to admit. Movies and television, in particular, make for great guilty pleasures.

We watch them when we’re sad, when we’re bored, when we’re laid in bed sick, or when we’re feeling stressed and just need to be uplifted for a moment. But what kind of movies are typically a guilty pleasure? Well, it’s usually something a person would be ashamed to admit publicly; in this sense, a guilty pleasure tends to be contextual.

What is a Guilty Pleasure?

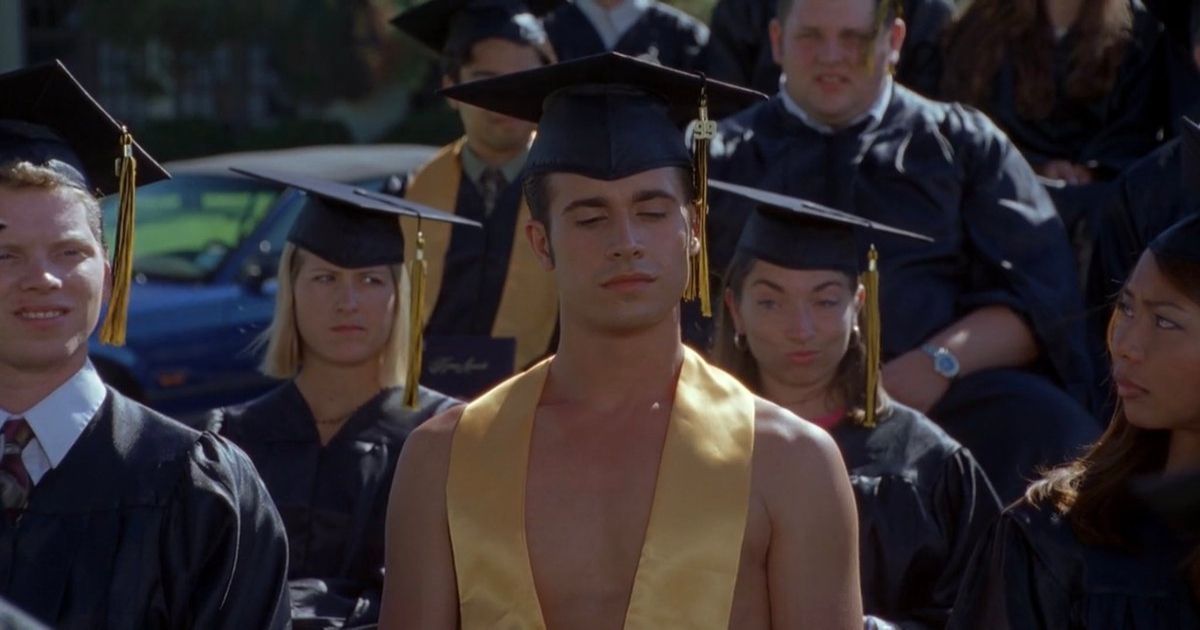

Maybe you’re an intellectual feminist, but you have a soft spot for sentimental, traditional, cheesy romance movies like Bridget Jones, 10 Things I Hate About You, She’s All That, or even The Proposal, movies you wouldn’t necessarily want people to associate with you. Maybe your co-workers all like critically acclaimed television like The Wire or Breaking Bad, and you’re ashamed to admit that you love The Bachelor. Maybe you’re a tough guy jock, but actually a closeted sci-fi movie lover who hides his massive comic book collection.

According to The New Yorker, before ‘guilty pleasure’ became a term, Aristotle believed that, “the pleasure associated with honorable action was virtue, whereas the pleasure associated with ‘evil action’ was vice — a genuine mix of guilt and pleasure by another name;” it was further described as “a need that is met.” In a way, guilty pleasures meet our needs, the desires we have that we’re often embarrassed about. But are guilty pleasures really an “evil action?” Not for us. These days, we are coming to terms with the idea, and we are beginning to announce our love for the guilty pleasures we would have once been so ashamed of admitting. We ask, should we even be feeling guilty for enjoying something in the first place? Let’s take a look at why we should be killing the term ‘guilty pleasure.’

Stop Conforming To Society

Perhaps the best way to describe how we feel when we refer to a guilty pleasure is shame; the phrase may be ‘guilty pleasure,’ but it should really be called ‘shameful pleasure.’ That’s because the feeling of guilt is often a positive thing; it’s a sign of a moral compass, and out guilt can turn into an action where we fix something we’ve done wrong. For example, if we hurt someone’s feelings, and then we feel guilty, we apologize. However, with shame, it often comes from a deep dark place within (generally imposed on us from without), where we haven’t necessarily done anything to deserve that feeling of impending embarrassment.

Pleasure refers to something that brings us joy, something that makes us happy or satisfies our senses, like a feel-good movie. Yet, why is it that just because others might not like it, we feel shameful about enjoying it ourselves? What is that voice in the back of our heads that says, “You shouldn’t be enjoying this?” Society. Society has taught us that we must confirm to the ‘norm,’ and if you are different, then you should feel guilty about it. It’s not just with movies, but also with lifestyles, and people have begun to even be unsure of their own judgments. This was explained further in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

“I would guess that the people who feel the most shame about their taste are the people who have been taught not to trust their own judgments already. Teenage girls, and queers, and people of color. Maybe we merely need to redistribute shame a little bit.”

To me, the essence of a guilty pleasure is a private or social acknowledgment of something’s badness, a momentary pause, and then pushing through that feeling toward pleasure anyway. It makes lots of room for cognitive dissonance. Academic analysis isn’t always so gentle. I thought for a long time that to apply academic attention to an object was to justify it or dignify it, but now I want to enjoy some of my favorite things without putting a high premium on dignity.

Eventually, after years of being told that things we enjoy are being deemed shameful by society, like watching reality TV or ‘nerdy’ movies, or even super gory horrors, we have begun to associate certain things with feeling guilty. We’ve been hiding ourselves away and keeping these awfully embarrassing secrets; by conforming to society’s standards and keeping our guilty pleasures under wraps, we become more socially acceptable than those who like the same things as us but aren’t ashamed to admit it. When this happens, we secretly wish we could scream it from the rooftops as well, but we don’t, and so we are more respectable within society’s hierarchy, but at a price.

Guilty Pleasures Are Self-Care

Enjoying these ‘guilty’ pleasures but being told that we can’t is confusing, and we shouldn’t be made to feel deep amounts of shame because of something that ultimately makes us feel happiness. In fact, the term ‘guilty pleasure’ is actually more damaging than the thing itself; it suggests that we don’t deserve to feel joy or happiness, or be emotionally stimulated by something without feeling bad about it.

Associating negative language with something that brings happiness confuses the brain and creates immense self-doubt, and it can become seriously hard to start enjoying anything again without asking ourselves, “Am I allowed to enjoy this?” We should instead be realizing that this is a part of ourselves that we shouldn’t ignore, just because we don’t fit into society the way that it wants us to; we have to learn to accept them and embrace them as part of our personality and full authentic self.

Perhaps we’ve all had enough; ‘guilty pleasures’ have ironically become popular in the last 15 years. It’s as if cracks have formed in the dams that society built up, which were blocking all the waters of our repression. One of the biggest examples of this is comic book media and the popularity of superhero movies. For many decades, these things were considered niche, childish, and dumb, and condescended to. The same went for video games and reality TV. In recent years, though, these things have become a huge source of entertainment.

Does this mean that we can stop feeling guilty about liking things now? Despite guilty pleasures becoming popular, the stigmatization around what is ‘cool’ or acceptable still remains. Even though now we can talk about the things we like, people are still being judged around their pleasures. In fact, sometimes the pendulum swings in the opposite direction; now, anyone who hates superhero movies or video games is looked at freakishly. This means that it really doesn’t make a difference whether we talk about our opinions or not, because we will still be criticized for it.

That’s the ultimate secret here — it isn’t about what someone likes or doesn’t like; it’s about how others judge it. The real problem isn’t with the media itself, but with how people criticize it. The advent of social media and comments sections has only exacerbated this, and it seems like people have forgotten that art is subjective. Instead, they criticize each other for liking or not liking something, assuming that their own personal opinion is objective fact.

To move culture forward, we need to stop shaming others for their pleasures. We need to kill off the term ‘guilty pleasure’ and stop feeling shame for enjoying things that we find fun and that make us happy, and we need to stop telling other people what is ‘good’ and what ‘sucks.’ Rather, we should be throwing ourselves into our own enjoyment as, most of the time, they help our mental health and can even be seen as a form of self-care, and we should be doing it without fear of judgement. Don’t tell others what to like; instead, like what you like, proudly and shamelessly.

[ad_2]

Source link