[ad_1]

The term “the fourth wall” originated in the theater, where a stage — enclosed by three walls — contains an imaginary fourth wall that marks the boundary of the on-stage action. In movies, the fourth wall exists to separate the story from the viewer, providing a more immersive experience.

Filmmakers will sometimes deliberately break the fourth wall as a way of disrupting the fantasy of a movie by introducing reality. While it is usually successful, it doesn’t always work (for example, Adam Sandler in Bedtime Stories). But, the cinematic technique can be used to great effect, making a scene funnier, cleverer, or, in some cases, more disturbing.

‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off’ (1986)

Sometimes breaking the fourth wall in a movie can disconnect audiences from the film’s characters and take them out of the story. This is not the case with the classic John Hughes comedy film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

Rather than disengaging audiences from the magic of the movie, Ferris Bueller’s (Matthew Broderick) to-camera delivery invites audiences along for the ride. By speaking directly to the camera, viewers are ushered into Ferris’ world instead of simply watching the action take place.

‘Wayne’s World’ (1992)

It will soon become obvious that one of the more successful uses of fourth-wall-breaking occurs in the comedy genre. And few comedies have done it more successfully than Wayne’s World.

Wayne’s World is an “excellent” meta-comedy that frequently breaks the fourth wall, a standout example being when Wayne (Mike Myers) underscores the absurdity of product placement in films. After proclaiming that “Contract or no, I will not bow to any sponsor,” in the space of a minute, Myers grins at the camera while holding a slice of Pizza Hut pizza, a packet of Doritos, a bottle of Nuprin, and a can of Pepsi.

‘Airplane!’ (1980)

The disaster film parody Airplane! is definitely made for laughs. However, there is one particular scene near the beginning of the movie that deals with a more serious topic: relationship breakups. In that scene, complete with string accompaniment, Ted Striker (Robert Hays) tries to convince his flight attendant girlfriend, Elaine Dickinson (Julie Hagerty), that they should resume their relationship. She ultimately rejects him and walks away, at which point Hays turns to the camera to utter, “What a pisser.”

This instance of fourth wall breakage not only provides a pithy punchline, making the scene funnier, but Ted’s outburst stands in stark contrast to the flowery, romantic language he used in trying to win back Elaine. It prevents the scene from devolving into a cheesy romantic trope and ensures the movie quickly gets back on its comedic track.

‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail’ (1975)

Those irreverent Monty Python boys were fond of breaking the fourth wall. In The Meaning of Life (1983), they made direct-to-camera commentary about the fact that they’d reached the middle and the end of the film. And in their earlier film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, they broke the fourth wall mid-scene.

In a true meta-moment, while Sir Galahad (Michael Palin) is speaking with Dingo (Carol Cleveland), Dingo asks the audience directly: “Do you think this scene should have been cut? We were worried when the boys were writing it, but now we’re glad! It’s better than some of the previous scenes, I think.” The scene is followed by a montage of other characters, also speaking direct-to-camera, urging Dingo to “get on with it.”

‘American Psycho’ (2000)

Comedies aren’t the only genre of movie to make good use of breaking the fourth wall. And, as American Psycho demonstrates, the technique can be achieved in ways other than direct-to-camera addresses by the actors.

American Psycho breaks the auditory fourth wall by having its main character, Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale), address viewers via a voiceover. In scenes like the one where Bateman and his over-achieving pals are comparing business cards, we hear what Bateman thinks while the on-screen dialogue conveys something completely different. Although Bateman is an unreliable narrator, the fourth wall break provides us with an insight into the workings of his psychotic mind.

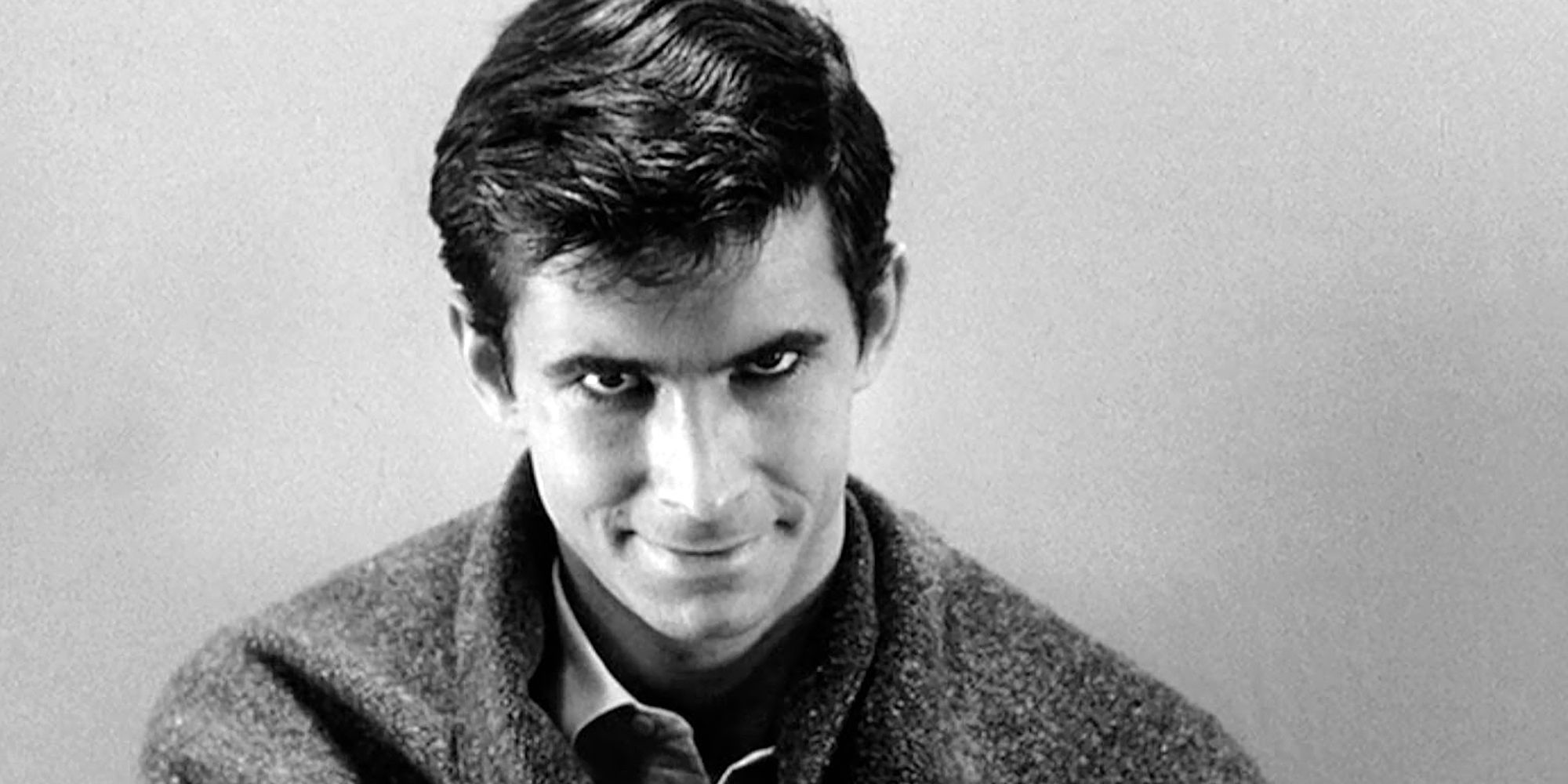

‘Psycho’ (1960)

Another movie that, through breaking the fourth wall, allows audiences a glimpse into the mind of a psychopath is Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

Anthony Perkins’ direct-to-camera stare at the end of the film – gazing up from under his eyebrows wearing the flicker of a smile while his “mother” provides the voice-over — has produced one of the most iconic and disturbing images in film history. The creepiness of that image is heightened by the skull superimposed over the face of Norman Bates as the movie cross-fades into its final scene.

‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971)

It’s an opening scene that is seared into the audience’s brains, and it’s all to do with director Stanley Kubrick breaking the fourth wall. Although Kubrick is no stranger to breaking the fourth wall — he does it in The Shining (1980) and Full Metal Jacket (1987) — he approached it differently in each of his movies.

In A Clockwork Orange, the first thing viewers are treated to post-opening credits is a full 20 seconds of Alex’s (Malcolm McDowell) unblinking, piercing stare straight into the lens as the camera pans out to reveal him drinking a glass of moloko (milk). As a scene, it perfectly sets up the disturbing dystopia that follows.

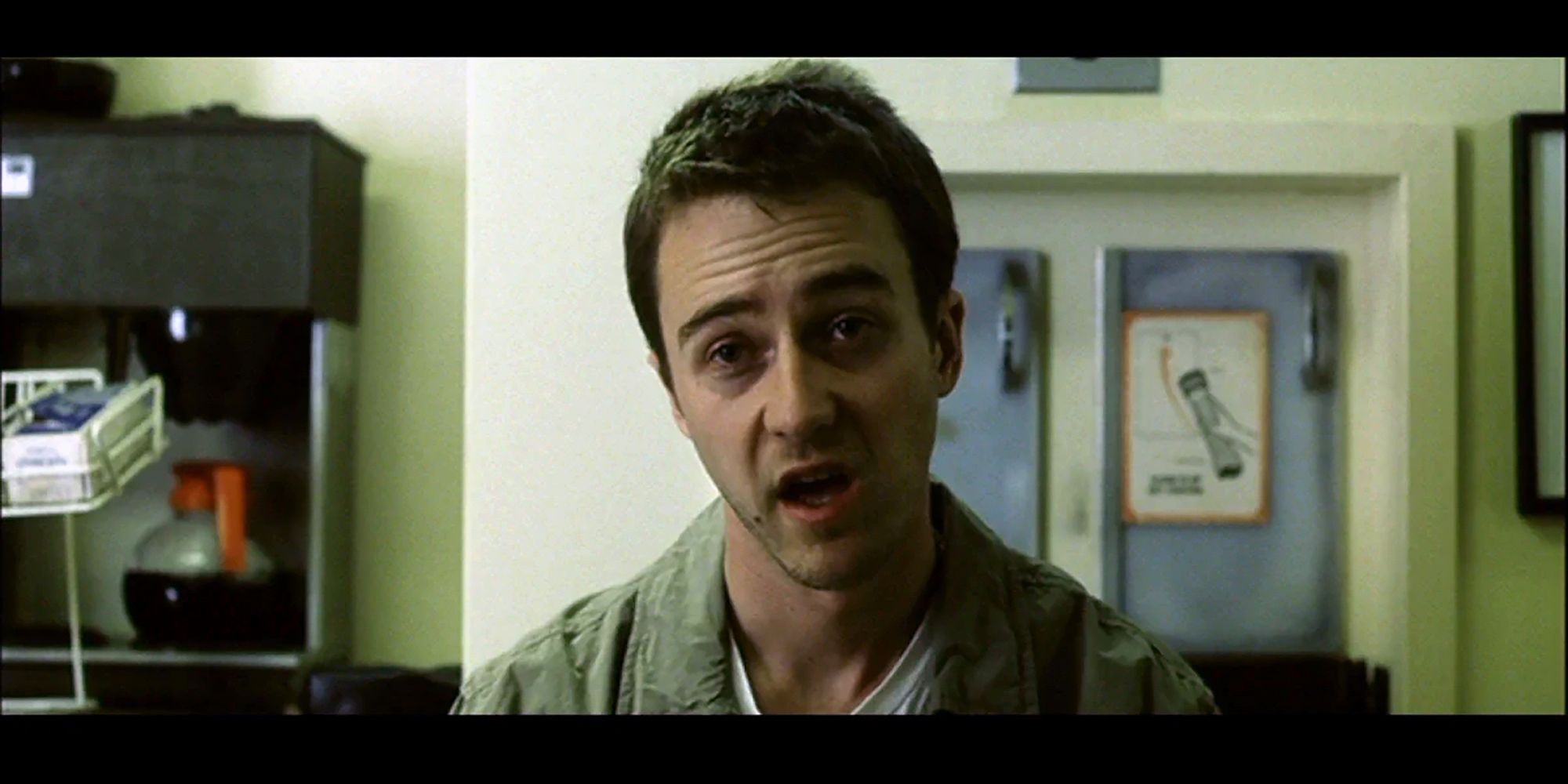

‘Fight Club’ (1999)

Another use of the fourth wall break is to convey a large amount of information to audiences about a complex character. Such is the case in David Fincher’s Fight Club.

By having the narrator (Edward Norton) break the fourth wall regularly throughout the movie — “Let me tell you a little bit about Tyler Durden” — Fincher enables audiences to come to grips with Durden’s (Brad Pitt) complicated character. The multiple fourth wall breaks are so seamlessly inserted that it’s easy to forget that Norton is addressing you directly.

‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ (2013)

As with Fight Club, in The Wolf of Wall Street the protagonist, Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio), regularly narrates the events in his life direct-to-camera.

Director Martin Scorsese has DiCaprio address the audience to let us know just what kind of man Belfort is: brashly confident and charismatic. This kind of breaking of the fourth wall, combined with the dynamic movement and placement of actors — something that Scorsese is famous for — helps connect the character to the audience.

‘The Big Short’ (2015)

Based on the book of the same name about the 2007 US housing market crash, The Big Short deals with many dense economic concepts.

In addition to providing on-screen definitions of certain terms, director Adam McKay decided the best way to communicate these concepts to audiences was to break the fourth wall and have various celebrities appear to explain them using metaphors. Enter the chef Anthony Bourdain, actress Margot Robbie, singer-songwriter Selena Gomez and economist Richard Thaler — among others — to school the audience.

‘Annie Hall’ (1977)

There are few filmmakers who break the fourth wall as often as Woody Allen does. His use of the technique in Annie Hall, along with the movie’s clever writing and storytelling, contributed to it taking out the Best Picture and Best Director Oscars in 1978.

A standout is the scene in which Alvy Singer (Allen) and Annie Hall (Diane Keaton) are waiting in line at the cinema while a fellow patron — a pompous academic played by Russell Horton — loudly critiques films behind them. When it becomes too much for Allen, he turns to the audience to complain. But the true brilliance comes when the annoying academic and Marshall McLuhan, the Canadian media scholar he’s been spouting off about, join in the fourth wall break. It’s scenes like this that make Annie Hall one of Allen’s best works.

‘Deadpool’ (2016)

The movie that takes breaking the fourth wall to a whole new level is Deadpool. Everyone’s favorite wisecracking mutant anti-hero, Wade Wilson aka Deadpool (Ryan Reynolds), frequently turns to audiences to share his opinion of the goings-on around him.

As Deadpool, Reynolds not only acknowledges the viewer but also references the outside world and the movie he’s starring in. Importantly, Reynolds’ fourth wall breakage never detracts from the movie’s plot. To make it even more fun for audiences — and a lot more meta — Reynolds cleverly spins a web of pop culture references, successfully merging the worlds of fantasy and reality: “Fourth wall break inside of a fourth wall break? That’s like… 16 walls!”

[ad_2]

Source link