[ad_1]

Gerda: A Flame In Winter is an incredibly error-prone game. When we see Nazis in games, we want to shoot them. But in Gerda you are forced to live next to them. You don’t have a gun and you’re not even a fighter. You are a nurse living in a German-occupied Danish village whose life during World War II consists of looking after your chickens and trying to gather enough rations to bake a cake for the church.

Civilian stories in World War II are often ignored or romanticized, tragically falling in love with brave, heroic soldiers or nameless victims used to add emotional impact. The UK is known for looking at its own wartime past with rose-tinted glasses, coining the term Blitz Spirit to encourage optimism in times of hardship.

For developer PortaPlay, the solution to all this historical revisionism and carelessness was simple: start with the truth.

“I think of my grandparents, they were resistance fighters near the village of Tinglev,” says Hans von Knuth, creative director. “They wanted to fight against the Nazi occupation, but not against individual Germans in uniform because they lived among a mixed population of Germans and Danes. They saw people, not soldiers.

“That dilemma of wanting to stand up to injustice, but also having moral limitations on what you can do, we found very interesting. Can you balance this? And can you make a difference without using force?’

Gerda, the titular character, is Danish and German, so the similarities are immediately apparent. The first characters you meet are Gerda’s father – a German and member of the Nazi party – and her husband Anders – a Danish resistance fighter. All you have to do is walk the streets and talk to everyone, Danes, Germans and Nazis.

Living alongside the Nazis in their uniforms, exchanging pleasantries while knowing the atrocities they were complicit in, can make for a frustrating experience at first, as if we were “both sides” in a genocide. Fortunately, this never happens. All Gerda as a game does is acknowledge that they were real people, neighbors and family members. We can’t escape it.

“We wanted to show a civilian in a violent conflict, caught in the middle. We used the Danish environment and history because there’s a lot of that stuff,” says von Knuth.

Having such a personal connection to the area through his grandparents, von Knuth explained that the setting helped the authenticity of the story. “We could show the context of ordinary people who had things to prioritize over being morally right. They had relationships, things they couldn’t sacrifice. That means it’s harder to stand up to oppression. And that was something we wanted to show.”

However, the people of the village are not the only ones who are clarified in Gerda’s story.

“We strive to humanize everyone,” says Shalev Moran, lead game designer. “There are monstrous acts, but there are no monsters. The worst things happen when people imagine they can’t do something terrible.

“We are not trying to justify ideologies. It’s not about understanding both approaches, it’s about understanding the people who are caught in the middle.”

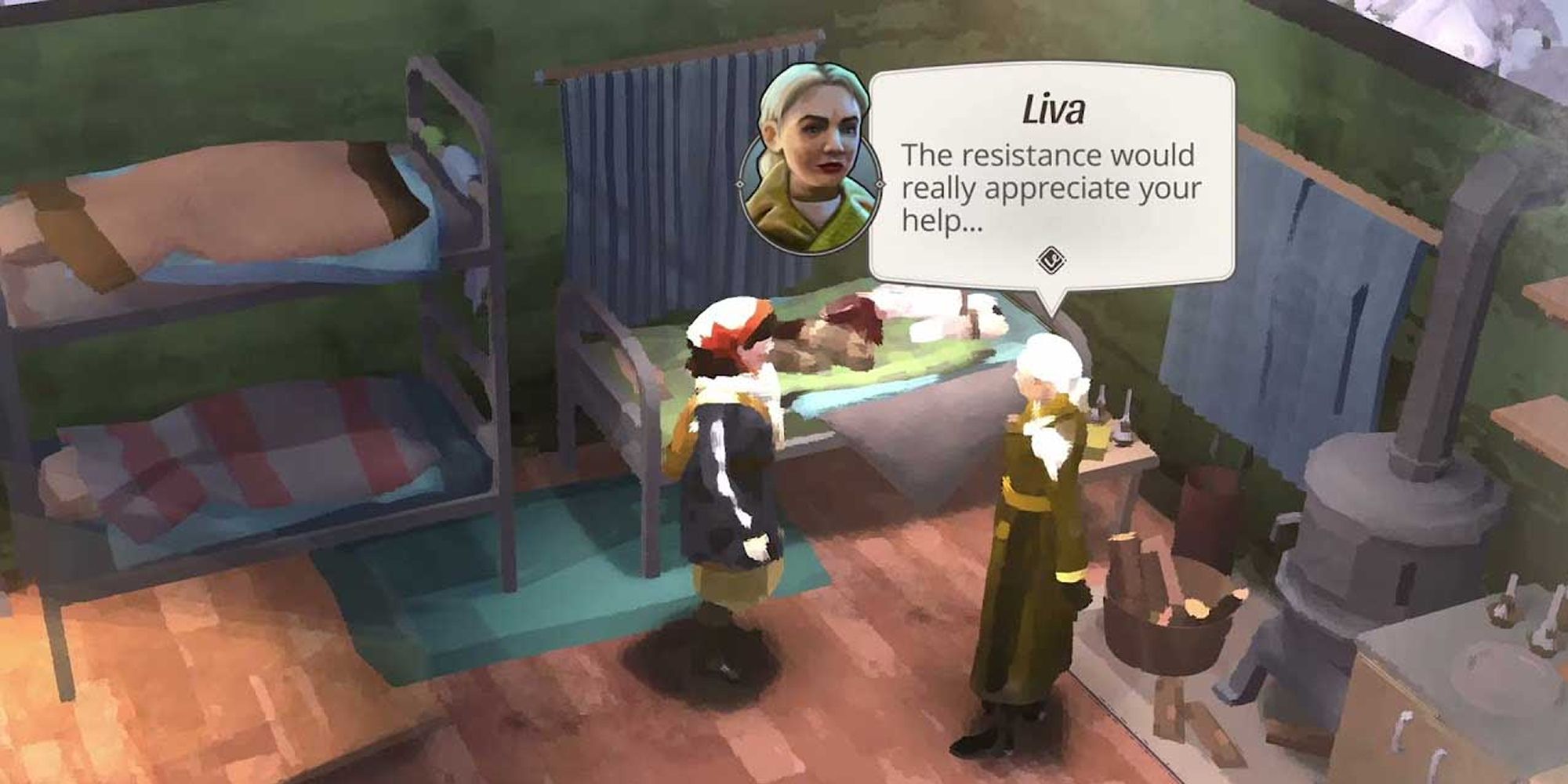

As many will likely do on their first playthrough, I decided to focus on helping a fleeing Jewish family and the underground resistance, but it quickly became apparent that this would be easier said than done.

“One of the things we want to shine a spotlight on is that people in real crises, where decisions actually make an impact, […] don’t get so clean,” says Moran. “You don’t have to be so clean, you have to get your hands dirty.

“Gerda fails to keep all her values. You should [decide] which values are more important.’

Gerda is not what Moran would call the “heroic narrative” we see so often in WWII stories. “[Hero narratives] they serve national interests, but that is also because they are very easy. Civilian prospects are not.”

At one point, you have the chance to steal the only dose of penicillin in the village. You can give it to a sick child, a wounded resistance fighter, or even a drug addict Nazi soldier in exchange for preferential Gestapo treatment for your imprisoned husband. However, even if you can come to terms with who you’re giving it to, it doesn’t negate the fact that you’re abusing your position as a nurse and stealing it from the only hospital in the village.

Even who you choose to donate your time to can be a morally gray choice. Do you help a Jewish woman get her fake passports or spend the afternoon supplying the resistance? Or do you neglect both jobs and focus on freeing your husband?

Even after all this, Gerda saves her worst moral dilemmas for her final moments, when the war is already over. (Endgame spoiler warning in the next two paragraphs).

During the epilogue, you discover that a trusted friend of yours has collaborated with the Gestapo. Depending on your actions, this betrayal could have resulted in dozens of deaths. The Nazis blackmailed him into helping them, of course, but if you’ve just spent the entire game resisting their pressure – and faced the consequences – why couldn’t he? it stings. In my game, Gerda lost everyone close to her because she devoted all her time to fighting the Nazis. I had no sympathy for the man who caused so much misery and betrayed him. Not surprisingly, he was shot on the spot.

“My grandmother was actually faced with this decision,” von Knuth says. “The informer who reported on her husband and sent him to a concentration camp was killed because she pointed him out. She regretted it afterwards. Maybe I’d like to punish him more like you. But I’ll still be sorry he died because it didn’t matter. We’d love for people to discuss these moral dilemmas.

“People look back on history and say, ‘Why didn’t they rebel?’ Why didn’t they overthrow the dictator?’ You weren’t there, you don’t understand how difficult it was, what pressure they were under.”

Many of us still think this way. You only have to look at those who tar all Russians with the same brush they paint Putin with to see that.

“Now you’re here, why don’t you do it?” Moran tells those who think that way. “Go there. Kyiv is one flight away.

“There is no need to condemn the Nazis. It’s easy, low-hanging fruit. What we want to do is put our players in uneasy circumstances. [We want them] to say “Oh shit. I make ethically uncomfortable decisions because I’m trying to improve people’s lives.”

But you’re not a superhero. Power, or the lack of it, is a huge theme in Gerda. Instead of having her level up and constantly get stronger, you have to use up your abilities every time you use them. They give you an advantage, but the results are still decided by dice rolls, which shows that no matter how hard you try, if luck is not on your side in war, people die. “She’s not a character who grows in power,” Moran explains. “She can tense up, which puts her in a worse position for the next chance roll. I tried to save some of my ability points. This of course causes a lot of bad things to happen during the game, which puts me in a worse social position towards the end.”

Gerda – along with This War of Mine – is part of a growing genre that depicts the ugly, raw truth of war. Not interested in power fantasies or heroism. Instead, you must face the impossible task of sticking to your morals when your life and those of your loved ones are at risk.

Gerda: A Flame In Winter is now available for PC and Nintendo Switch.

[ad_2]

Source link

.png)

.png)

.png)