Introduction

Medical malpractice is a major cause of mortality and morbidity globally, with significant consequences for healthcare systems, communities, and providers. Malpractice claims negatively affect physicians’ well-being, leading to burnout, depression, and suicidal thoughts, as demonstrated in a study including 25,000 surgeons.1

Despite physicians valuing legal knowledge, their understanding of medical law remains limited. Therefore, integrating medical law training in undergraduate and postgraduate education is crucial.2 Numerous researchers have advocated for incorporating medical law and ethics fundamentals into medical school curriculums. Attaining this knowledge enhances medical professionals’ critical thinking skills and decision-making prowess throughout their practice, thereby enabling them to address diverse clinical challenges in an ethically, legally, and professionally justifiable manner.3

Incorporating Islamic Medical Jurisprudence into the medical school curriculum enhances the caliber of medical practice.4 It standardizes general practice within Islamic communities that regard the Quran and Sunnah of Prophet Muhammed as fundamental sources. In 2005, the Saudi Arabian government implemented the Medical Liability Law, establishing a legal framework for patients seeking remuneration due to medical malpractice or negligence.5 Nevertheless, a notable increase in legal, medical claims was observed by the Sharia Medical Panels (SMP), with reported cases escalating from 2002 in 2012–2013 to 3043 in 2015–2016.6 Consequently, there is a critical necessity to reinforce and safeguard the community’s rights concerning medical errors in healthcare environments.

To augment healthcare quality and bolster patient safety, the Saudi Arabian government instituted the Saudi Commission of Health Specialties (SCFHS) in 1992.7 The SCFHS is responsible for regulating healthcare professions within the nation, licensing practitioners, and addressing diverse facets to ensure high-quality healthcare training. The Saudi Board of Emergency Medicine (SBEM) program, initiated in October 2001, is among the most prominent residency-training programs governed by SCFHS.8 The SBEM curriculum adheres to the Can MEDS9 roles framework competencies encompassing medical expert, communicator, collaborator, manager, health advocate, scholar, and professional. The objectives of this study include an investigation into the existing educational approaches of legal and bioethical topics within the Saudi Board of Emergency Medicine (SBEM), as well as an examination of key stakeholders — program directors and trainees — perceptions regarding the incorporation of a legal and bioethical education module into the current curriculum.

Aim

The objective of this study is to investigate the present educational methodologies concerning legal and bioethical topics within the Saudi Board of Emergency Medicine (SBEM) curriculum and to examine the perspectives of significant stakeholders (including program directors and trainees) on the incorporation of a legal and bioethical educational module into the existing curriculum.

Objectives

- Examine the current pedagogical approaches in SBEM concerning legal and bioethical issues, encompassing: selected subject matter, instructional methods, assessment methods, resource materials for study guides, and roles of participating individuals.

- Investigate the perspectives of both program directors and trainees within SBEM regarding incorporating a well-established legal and bioethical module into the existing curriculum.

- Identify the most appropriate instance for incorporating the legal and bioethical module into the current SBEM curriculum.

Methods

Study Design and Sampling

The study was conducted utilizing a qualitative research methodology. Key stakeholders, whose perspectives were pertinent to the objectives of this study, were identified and engaged in the process. These stakeholders included:

- SBEM program director: As delineated by the SCFHS,10 a proficient, licensed specialist responsible for overseeing a specific training program within a training center.

- Trainee: As stipulated by the SCFHS,10 an individual who has been accepted into and enrolled in an approved training program governed by the SCFHS.

A purposive sampling technique was used. A total of 19 participants (comprising seven program directors and 12 trainees) were involved in this study, originating from various training centers throughout the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The trainees represented a range of training levels, spanning from level one through to level four.

Data Collection

The approach utilized for data gathering contained comprehensive, in-depth interviews. Participant recruitment endeavored through various channels such as email and WhatsApp invitations, direct personal communication, and telephonic conversations. The lead researcher is an emergency medicine consultant with over five years of experience in the field and serves as the deputy program director at her training center. Utilizing her professional connections, she reached out to program directors. Subsequently, she contacted program educational coordinators and directors for access to the trainees. In some cases, she directly approached trainees within her workplace.

The lead researcher primarily executed the interviews utilizing virtual means, supplemented by nine in-person interviews conducted at the participant’s place of work. Upon consenting to participate in the study, the participants underwent interviews lasting between 30 to 60 minutes, with each session being audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The interview questions were devised in accordance with the research objectives by the lead researcher. Two Medical Education specialists assessed these inquiries (refer to Appendices 1 and 2 for further details). Separate interview guides were created for program directors and trainees, given their distinct perspectives. The questions were designed to be open-ended, thereby encouraging the provision of extensive information. Throughout the interviews, supplementary questions were posed as needed to elicit clarification and additional specifics.

The participants were not consulted regarding the findings, except in a single encounter. This was done to address one trainee’s feedback about the presence of a designated module covering ethical and legal issues. The approach taken was professional in nature.

Additional demographic variables were gathered, incorporating factors like gender, age, geographical area, educational institution, number of trainees at each location, program directors’ duration of experience and sub specialization, and trainees’ level of education. The investigation’s questions examined the existing bioethical and juridical instruction within the scope of SBEM from both program directors’ and trainees’ standpoints. Moreover, it aimed to discern their opinions concerning integrating a bioethical and legal pedagogical module into SBEM’s future curriculum and identify the optimal timing for such a module’s introduction.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted concurrently with data collection. The lead researcher meticulously transcribed each recorded interview. Utilizing a constant comparative method, data were continually assessed and analyzed, culminating in theoretical saturation. Initially, two research team members independently examined the first eight transcripts, identifying emerging themes and conducting open coding. Subsequently, they convened to discuss and compare their results, ultimately devising the initial open coding structure consisting of numerous codes and sub-codes. As additional interviews took place, this coding framework was implemented by the research team members and modified as new topics emerged. This approach was applied to the remaining interview transcripts.

The researcher continued the interviews until they detected a consistent pattern in the responses from the participants. When they observed this recurrent pattern, they declared that data saturation had been achieved and decided not to proceed with any more interviews.

Subsequently, a third research team member reviewed the open codes, progressing to axial and selective coding alongside the rest of the team. The main themes and subthemes were then established, concentrating on the needs assessment for incorporating a bioethical and legal module into the existing SBEM curriculum from the perspective of two primary stakeholders (program directors and trainees). Finally, connections among categories were identified, and categories were refined to determine central themes. The research team engaged in discussions to evaluate thematic categories and their interrelationships.

Ethical Approval

The study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (IRBC/1933/20). Before conducting interviews, verbal consent was obtained from each participant, encompassing their involvement in the study and video and audio recordings. Participation was voluntary; thus, individuals faced no penalties for refusing to take part or declining to answer specific questions. No identifiable information, such as names, email addresses, or IP addresses, was collected. Transcript data, video footage, and audio recordings were stored securely without identifiers on the researcher’s computer. Following data analysis, the researcher deleted the recorded videos and audio. No transcripts were sent back for review; there were no repeated interviews or refusal to participate in the research.

Results

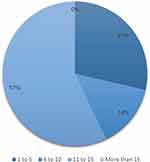

The study encompassed 19 participants, seven program directors, and 12 trainees (n=19), with a gender distribution of 13 males and six females. Most program directors are associated with educational institutions that accommodate over 20 trainees. The average experience of the program directors as emergency medicine consultants range between 11 and 15 years (Figures 1 and 2). Geographically, one program director was interviewed from Jeddah and the Eastern Province, while the remainder were based in Riyadh. Of the trainees, one hailed from the Eastern Province, one from Jeddah, and the rest from Riyadh. Subspecialties among program directors included Disaster Medicine, Point of Care Ultrasound, and Toxicology. Additionally, two program directors possessed Master’s degrees in Medical Education and fellowships in Medical Simulation. Trainee participants spanned various training levels; five junior and seven senior-level trainees were interviewed, aged between 25 and 30.

Figure 1 Number of trainees in the training centers. Most trainees participating are from training centers with over 20 trainees. Among the centers, 14.3% accommodate 11 to 15 trainees, and 14.3% have fewer than six trainees. |

| Figure 2 Program Directors’ Years of Experience: The majority of program directors in the study have over ten years of experience as consultants in emergency medicine. Of the participants, 29% had less than 5 years of experience, while 14% had between 6 to 10 years of experience. |

Existence of Identified Educational Module for Bioethical and Legal Subjects in the SBEM and the Current Educational Practice

Officially in the Saudi board, there is no curriculum for law and bioethics. (PD2)

| Table 1 The Themes and Subthemes That Emerged from Participant Feedback Regarding Integrating a Bioethical and Legal Educational Module in the Current SBEM Curriculum |

Theme One: Planning the Current Bioethical and Legal Educational Activities in the SBEM

The Control of Current Educational Activities

Role of Program Directors, Trainers, and Senior Trainees in the Educational Process

Lack of Awareness

Theme Two: Teaching Methods and Guiding Resources in Bioethical & Legal Education

Instructional Method

Guiding Educational Resources

Theme Three: Current Assessment Methods in Bioethical & Legal Education

Theme Four: Opinions Regarding Integrating Bioethical & Legal Educational Module in SBEM

Discussion

- The fundamental Islamic Bioethical and medicolegal standards that all trainees must acquire prior to completing their studies.

- Observations gathered by program directors and trainers during their clinical practice, focusing on frequently occurring issues they hope trainees will prevent in their future work.

- Singular incidents that program directors and trainers view as valuable learning experiences and impart to their trainees.

- Personal experiences shared by program directors and trainers themselves.

- Hospital documents related to mortality and morbidity cases, legal claims, and patient complaints.